- PATIENT FORMS | REQUEST A CONSULTATION | CONTACT US

- 1-844-NSPC-DOC

IT’S ALL ABOUT THE DECOMPRESSION…

YOU DON’T HAVE TO GET EVERY MORSEL

January 6, 2025NSPC CEO Dr. Michael Brisman Addresses 2025 MSSNY House of Delegates

April 11, 2025

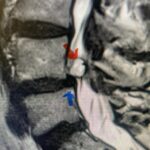

Fig 4: Sagittal T2-weighted cervical MRI demonstrating a significant disc osteophyte complex causing spinal cord compression at C 5 6 with extensive myelomalacia (red arrow)

One of the things I look forward to every week is being able to walk my chocolate lab, Leo, in Central Park. They let you take the dog off the leash before 9 am. I particularly enjoy this on weekends because it gives me time to think. Among many other thoughts, I have about my four kids and their situations, I often think about spine surgery and what I just did this past week. I think about how I could do things even better or differently or just think about what I just did with my trusty orthopedic spine surgeon. I realize what I am most interested in my career at this point being 59, is decompressing degenerative material off the dura. This seems to be our niche and what we do best. I think about patients who have degenerative compression of their nerves or spinal cord such as those with lumbar or cervical stenosis, respectively. I think about the main concerns of patients when they ask me questions about their surgery, particularly in those cases that involve a concurrent fusion. I tell patients that the real art of the surgery is to get the nerves and spinal cord decompressed from this compressive arthritis without injury or leakage of spinal fluid. Putting in the hardware and the fusion is in my opinion the more straight-forward part of the surgery, not to say hardware placement can’t be challenging. So looking back on the last month or so this is what we did and here are some illustrative cases:

This 62 year-old female who had a prior ACDF from C3-C7 by an outside surgeon in 2009 and subsequent C5-C7 posterior cervical decompression and fusion in 2015 by our team, presents with progressive numbness, pain, and weakness of her arms. Above her prior anterior fusion, she had next segment degeneration with spinal stenosis resulting in spinal cord compression at C2-3 (Fig. 1).

Patient had an existing peripheral occipital nerve stimulator and therefore we had ordered a myelogram since it was not MRI compatible. The patient underwent a decompressive laminectomy and in situ fusion at C2-3. Care was made to preserve a good portion of the C2-3 facets bilaterally. It was felt that her C2 pars anatomically were not favorable to accept pars screws given the proximity of the vertebral foramen with a resultant narrow par (Fig. 2). She also had a normal C2-3 vertebral alignment. Post-operatively she had improvement of her arm pain and strength in right arm. In this case we made a decision to decompress the patient posteriorly given her prior anterior surgery, a more difficult approach to C23 disc space, and significant C23 disc collapse. A posterior approach was favorable in our opinion given the prior posterior surgery was more inferior with less scarring likely to be encountered in the C1-3 region. A posterior decompression also can yield a more adequate spinal cord decompression. Since we elected not to place pars screws because of her anatomy, and perform an in-situ fusion, careful attention was made to preserve as much of the C23 facet complex as possible.

Fig 1: Sagittal cervical CT myelogram demonstrating spinal cord compression at C2-3 above the prior anterior cervical fusion (red arrow)

Fig 2: Sagittal cervical CT pyelogram demonstrating a very narrow C 2 pars and prominent vertebral foramen making in unsafe to place a pars screw

A 37-year-old male police officer complained of a one-month history of difficulty with his balance and leg weakness. He complained of achiness in his legs. He also complained of bilateral arm weakness and numbness of his hands. He was also having difficulty writing due to the weakness. Patient had an MRI of the cervical spine which demonstrated a disc/osteophyte at C56 causing spinal cord compression and concurrent myelomalacia (Fig. 3). Patient underwent an anterior cervical discectomy with a cage and plate (Fig. 4). He tolerated the procedure well with improved numbness and weakness. This is a young person with fairly extensive myelomalacia and a fairly rapid development of symptoms. For this it was felt surgery was indicated. How he will do will depend on how much of his symptoms was caused by the compressive component or intrinsic damage to the spinal cord. As a rule, patients generally improve to some extent quickly; but their recovery of their spinal cord function can sometimes take up to 2 years to realize the extent of their improvement. Patients have to be patient with themselves in terms of their expected recovery.

Fig. 3: Sagittal T2-weighted cervical MRI demonstrating a significant disc osteophyte complex causing spinal cord compression at C 5 6 with extensive myelomalacia (red arrow)

Fig. 4: Intraoperative lateral cervical x-ray demonstrating anterior cervical construct in good position at C 5 6 (red arrow)

This 65-year-old male had classic neurogenic claudication with pain and heaviness in his legs when he walked and stood, but he improved when he sat or leaned on a shopping cart. Lumbar MRI revealed that the patient had severe stenosis at L4-5 with degenerative collapse and retrolisthesis (Figs. 5a & b). The patient had failed all means of conservative management including physical therapy and epidurals. He was indicated for a laminectomy and instrumented fusion at L45 because of his chronic instability at that segment and the degree of facet removal in order to adequately decompress him (Figs. 6a & b). The patient tolerated the procedure well with improvement of his leg pain. When there is a loss of cartilage of the disc space and the development of ligamentous laxity with resulting anterior or retrolisthesis, the spine is signaled to develop compensatory mechanisms to auto-stabilize itself. The spine compensates by enlarging the facet joints often resulting in physical calcified extensions that close off the spinal canal. The ligamentum flavum will often thicken so much that it too causes severe stenosis. This flavum is important in helping to keep the spine upright. When there is a failure of stability this ligament compensates by thickening. These compensatory mechanisms result in collateral damage to the nerves as if the spine itself is working independently of the neural structures.

This is a case of a 61-year-old male who presents with one year of severe neck pain that radiates into the upper extremities. He also complains of numbness in fingers and describes his strength as being “off” and with decreased grip strength. He has trouble sleeping because of the pain. He had tried anti-inflammatory and Physical Therapy. Cervical MRI revealed significant lateral osteophyte disease at C3-4 and C4-5 with severe bilateral foraminal compression (Figs. 7a & b). The patient underwent an anterior cervical discectomy with an interbody cage and plate (Fig. 8). Although it appears on axial images these two little extensions of bone, they are often more challenging to remove than appears. The trick to really get under these osteophytes so that the foramina can be decompressed well is to get under the posterior longitudinal ligament, expose the epidural space so that an obvious plane is created with fine Kerrison above the spinal cord dura. The patient tolerated the procedure well with decreased pain and numbness.

Fig 8: Lateral intraoperative cervical x-ray demonstrating good position of interbody cages at C 3-4 and C 4 5 with anterior cervical plate (red arrow)

This 43 year-old female presents to ER with severe right leg pain and weakness. She was unable to get comfortable in any position. She had taken anti inflammatories and had a recent epidural which did not help improve her radicular symptoms. She had ⅘ weakness in her right dorsiflexor, EHL, and plantar flexor. MRI revealed two-level disc disease with a massive extruded right L5-S1 disc herniation, most likely because of her severe acute radiculathy (Fig. 9A & 9B) She also has a large right L4-5 disc/osteophyte protrusion. It was felt that she should undergo an L4-S1 laminectomy and in situ fusion. We removed a massive L5-S1 disc fragment, dissecting a massive cavity underneath as well as above the posterior longitudinal ligament. We treated the right L4-5 protrusion as a lateral recess stenosis and decompressed well the descending right L5 nerve root. The patient had complete resolution of her radiculopathy and strength.