- PATIENT FORMS | REQUEST A CONSULTATION | CONTACT US

- 1-844-NSPC-DOC

WE LIKE TO DO IT ALL

NSPC CEO Dr. Michael Brisman Addresses 2025 MSSNY House of Delegates

April 11, 2025Dr. Jonathan Brisman Says Billy Joel’s “Brain Disorder” is Treatable

May 27, 2025

We have had a busy couple of weeks doing all kinds of interesting spine cases. WE LIKE TO DO IT ALL….particularly those cases that are degenerative conditions of the spine. Not only do we like to do primary or virgin bread and butter cases, but also, we love to dissect the needed scarred-in plane underneath the lamina of the patient with next segment stenosis after a lumbar fusion. The later scenario, for example, is amongst the toughest types of cases we do as spine surgeons. The true art of performing revision cases is to safely decompress significant arthritic formation resulting in stenosis commonly of the next segment. Since in these cases we often extend the fusion above, we can safely remove the inferior processes of the segment above with impunity to begin to open up important planes of dissection. One great maneuver is to use an up-biting curette by inserting it in the joint space and lifting the inferior facet. My orthopedic spine surgery colleague loves this maneuver. This helps to define the plane underneath the lamina from the scarred dura which allows to start the decompression. It also gives us an opportunity to remove the inferior facet more easily with Leksell and Kerrison punch, which allows critical access to the foramina and decompression of the descending nerve roots.

Most of what we do is really to remove compressive arthritis from the dura safely, without damaging the nerve or spinal cord and trying to avoid getting a spinal fluid leak. Here are some nice cases that illustrate what we type of cases we encounter on a weekly basis:

CASE STUDY

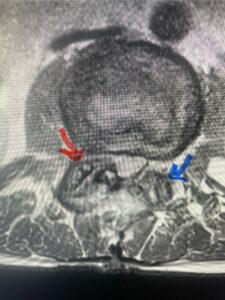

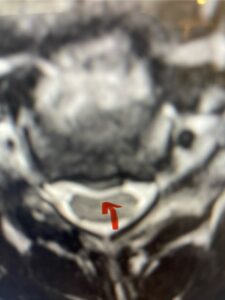

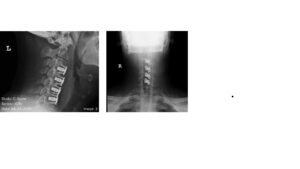

This 61-year-old female with a history of severe osteoporosis and a prior history of a laminectomy from l2-S1 with an L5-S1 instrumented fusion, presents with progressive low back pain and right lower extremity radiculopathy. MRI revealed a grade 1 L2-3 spondylolisthesis with severe stenosis mainly from severe right L2-3 facet joint hypertrophy which was compressing the right L3 descending nerve root. (Fig. 1). She had failed conservative management consisting of physical therapy and pain management with epidurals. She underwent an L1-3 revision laminectomy where we had to dissect a plane underneath the inferior aspect of the L2 lamina. We performed an instrumented fusion at L2-3 with special hydroxyapatite-coated screws to improve fixation to surrounding bone given here severe osteoporosis (Fig. 2) This worked out well and the patient had an uneventful recovery with relief of her leg pain.

Figures 1a: Sagittal and axial T2-weighted lumbar MRIs demonstrating a grade 1 L2-3 spondylolisthesis (red arrow) with severe stenosis secondary to right L2-3 facet hypertrophy (red arrow).

Fig 1b: Note the left L2-3 facet joint (blue arrow) is normal in size compared to the right (red arrow)

Fig: 2a: AP and lateral intraoperative fluoroscopic images demonstrating good placement of L2-3 pedicle screws

Fig. 2b

I still love talking about herniated discs. We think when we hear about such a case, we think simple. There is a major learning curve in doing one of the most straightforward and common problems we encounter as spine surgeons. I remember my chairman of my training program relayed the discussion between him and another famous neurosurgeon sitting at a bar during a neurosurgical meeting and saying to the other surgeon, “I think I know how to finally take out a disc”. This is to say that such a simple thing as removing a disc is not so simple and requires years of experience to really master the technique. The problem has to be addressed correctly and should not be taken lightly as there are important considerations in removing the disc fragment safely and successfully. There are often thoughts of whether the patient should in addition be fused from the beginning. Certainly Dr. Cloward, the famous spine surgeon, had his thoughts on this topic and felt a good percentage should have the disc removed and replaced with an interbody fusion spacer and instrumentation to avoid the possible resultant low back pain from chronic instability and described micromotion of the spinal segment.

NEXT CASE STUDY:

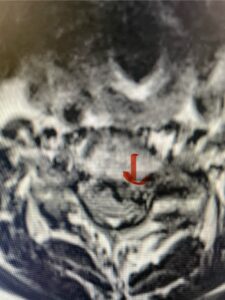

In this next case, this patient is a 47 year-old female who presents with intractable low back pain with severe pain, numbness, and weakness in the right lower extremity that had gotten progressively worse over a year. The patient had failed conservative management including physical therapy and epidurals. She was noted to have ⅘ weakness of plantar flexion. MRI demonstrated a large right L5-S1 disc herniation with severe compression of the descending right S1 nerve root (Fig 3). It was decided to perform a right L5-S1 hemilaminectomy for removal of the disc fragment and decompress the S1 nerve root. When you expose the disc, one must be certain to release any anterior adhesions to the nerve root in order to prevent a dural tear during retraction of the nerve root. It is also important to make sure during exposure and you finally encounter the dura after removing the ligamentum and fat, to make sure you are looking at the nerve root and not the main trunk of the thecal sac because if you don’t you can avulse or damage the nerve root if you retract the wrong structure.

Fig. 3a: Sagittal and axial T2-weighted lumbar MRI images demonstrating large right L5-S1 disc herniation (red arrows)

Fig. 3b

We found a massive subligamentous herniation which had to be revealed by having your partner retract the freed nerve root with a nerve root retractor and putting slight downward pressure on the more medial and anterior disc space. There is nothing more satisfying when the jelly (disc fragment) of the annulus (donut) comes squirting out and you remove a large chunk of disc material that clearly was stretching the ligament membrane and compressing the nerve root. This does cause back pain in addition to radiculopathy not only by the component of mechanical compression but also the stretching of the nerves within the ligament. We performed this surgery and noted that the nerve root was a very angry red color or hyperemic and we removed a large subligamentous fragment. The patient had improvement of her preoperative radicular symptoms.

Another point about disc herniations is the response to an epidural in a patient with an extruded disc beyond the posterior longitudinal ligament or contained within the subligamentous compartment. The reason being is that there is an inflammatory component to the radicular pain that is the result of a significant change in the biochemical environment from the disc material being released beyond its containment. With this change I wonder if a disc that is extruded beyond the ligament would in theory release more mediators into the epidural environment and therefore have more of a chance to respond to an epidural steroid injection? Is it possible that explains her diminished response to an epidural and thus requiring surgery to relieve the mechanical component of her pain?

Another patient, a 77 year-old female, presents with pain, numbness, and weakness of her arms and difficulty with balance over a 6-month period. MRI revealed severe osteophytic disease at C5-C7 with cord compression (Fig. 4). Further work-up by fine-cut cervical CT to evaluate the nature of compression revealed a completely calcified osteophyte (Fig. 5). Although the patient had a good lordosis and a posterior cervical approach would accomplish an adequate decompression, we elected to perform a two-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. This particular osteophyte is formidable because of its size but the compression was all anterior and would be a less invasive approach. Fortunately, during the procedure, the patient had a fair amount of osteoporosis which allowed the osteophyte to be drilled and bit away with considerable ease. Interestingly, the C6 7 osteophyte which was more a sheet of osteophyte was more challenging to remove. In the end the decompression went well, and we placed two interbody devices filled with bone graft with plates at each level (Fig. 6). The patient had a nice recovery with immediate reduction of pain and numbness. This case demonstrates the importance of recognition of cervical myelopathy in its early stages. A significant reversal of function is generally the rule if the patient has appropriate correlative findings on exam and MRI, particularly with long tract distribution weakness development within a year time period.

Figs 4a: Sagittal and axial T2-weighted cervical MRIs demonstrating large osteophyte worse at C5-6 compressing spinal cord more eccentrically to the left (red arrows)

Fig 4b

Fig 4c

Fig 5a: Sagittal and axial cervical fine-cut CT scan demonstrating severe osteophyte formation causing cord compression at C 56 (red arrow)

Fig 5b: Sagittal and axial cervical fine-cut CT scan demonstrating severe osteophyte formation causing cord compression at C 56 (red arrow)

Fig 6: Intraoperative lateral cervical x-ray demonstrating placement of interbody cages and plates

The case illustrates a more subtle finding of cervical myelopathy in a young 52 year-old male who presents with 5 months of left upper extremity weakness and burning. He also had developed over the last two months pain in his right upper extremity. He also had difficulty with fine motor skills. He had a positive Hoffman reflex and mild 4-4+ long tract weakness of his left arm and leg. Cervical MRI revealed an explanation for the patient’s symptoms (Fig. 7) as it revealed a disc osteophyte complex causing some cord flattening, slightly more to the left. We performed a C5-6 anterior cervical discectomy and interbody fusion with cage and plate (Fig. 8) He had a significant improvement in his weakness, numbness, and pain. What is interesting is that this was a relatively young patient without severe cord compression but was significantly affected by a mild amount of cord compression. This may speak to how a younger spinal cord may react much more adversely perhaps secondary to a less compliant spinal cord.

Fig. 7a Sagittal and axial T2-weighted cervical MRI’s demonstrating spinal cord compression slightly to the left secondary to disc/osteophyte complex (red arrow)

Fig. 7b

Fig 8: lateral intraoperative cervical x-ray demonstrating placement of interbody cage and plate at C5 6 (red arrow)

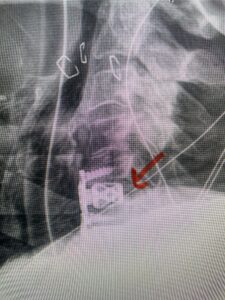

The next patient is a 54 year-old male who presents with 3 years of neck pain with associated numbness and tingling of his extremities. Patient had had physical therapy, chiropractic care, and epidural steroid injections with no significant relief. The patient on exam had weakness in a long tract distribution on the left. MRI revealed four level disc disease from C3-4 to C6-7 with a moderate kyphosis and cord compression and signal change at C3-4 (Fig. 9). Because of the kyphotic deformity it was decided to perform a four-level anterior cervical discectomy and interbody cage at each segment as well as plate. The patient had significant osteophyte disease at each level which required a high-speed drill to shave down the osteophytic disease and remove and decompress the foramina with fine Kerrison. Intraoperative imaging revealed good placement of the cages and plate at each level (Fig. 10). The patient had good relief of his preoperative symptoms.

Fig. 9a Sagittal T2-weighted cervical MRI demonstrating severe upper cervical spinal cord compression secondary to C2 anterior subluxation on C3 with development of thickened posterior degenerative material (red arrow)

Fig. 9b

Fig. 9c

Fig 10a and 10b: Lateral cervical x ray demonstrating placement of C3-C 7 interbody cages and plates.

For me, it was unusual to feel a need to perform a four-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. With patients who have more than three affected segments, I often try to perform a posterior decompression. It is not only easier but also avoids the swallowing risk and necessary multi surface fusion of a multilevel anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Because the patient was a bit kyphotic and had disease at all of these levels, I found it necessary to include all four levels anteriorly to effectively decompress the spinal cord and nerve foramina.