- PATIENT FORMS | REQUEST A CONSULTATION | CONTACT US

- 1-844-NSPC-DOC

Sometimes It Is Obvious And Sometimes It Is Not

Lateral Recess Stenosis

May 27, 2022

Cysts

July 2, 2022

Figure 5 Sometimes WJS

Patients sometimes have subtle anatomical abnormalities you discover as you investigate their problem. And sometimes these findings can answer the why and the how as to the cause of their pain syndrome. Patients, however, most commonly have an obvious cause of their complaint.

This 42-year-old female presented after complaining of low back pain with intermittent pain going down her left leg and numbness of her feet. She reported having a fall on her back about ten years ago and since then has had back pain. On exam, she had ⅘ weakness of her left dorsiflexion and extensor hallucis longus weakness. MRI revealed a “garden variety” L4-5 grade 1 spondylolisthesis with stenosis, although it was read as having a left pedicle “stress reaction” and suspicion of bilateral spondylotic defects. This was an interesting reading of the MRI, as it is uncommon to have spondylotic defects at L4 which occurs 5-15% versus at L5 which occurs in 85-95% of cases. Most people have an L5-S1 spondylolisthesis with an L5 pars defect. There was thickened ligamentum flavum worse on the left adjacent to the facet with concentric stenosis and bilateral foraminal stenosis. She had tried physical therapy and epidural injections, which did not help. She had trouble standing for long periods of time. Neurologically, she was intact.

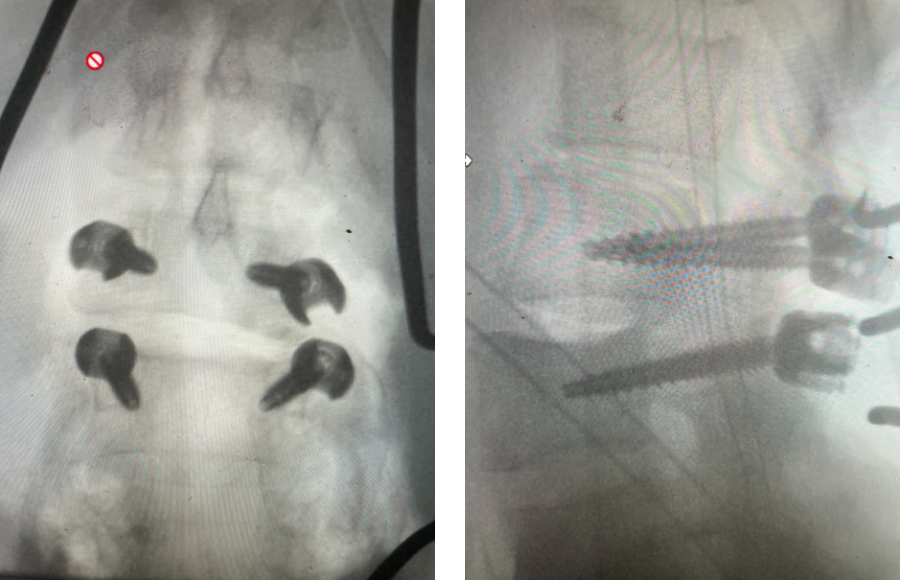

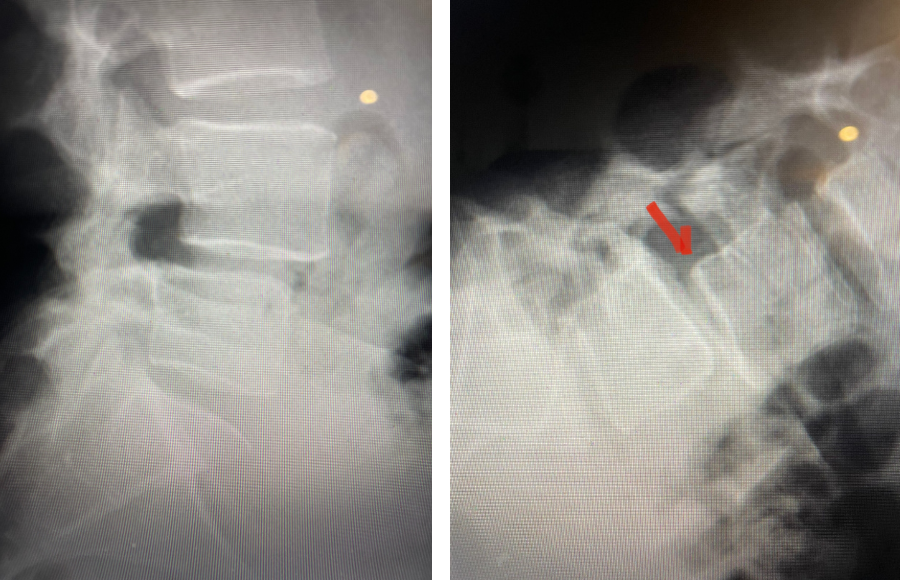

Fig 1: Plain X-rays demonstrating a grade 1 L45 spondylolisthesis with dynamic translation of approximately 4 mm (arrow).

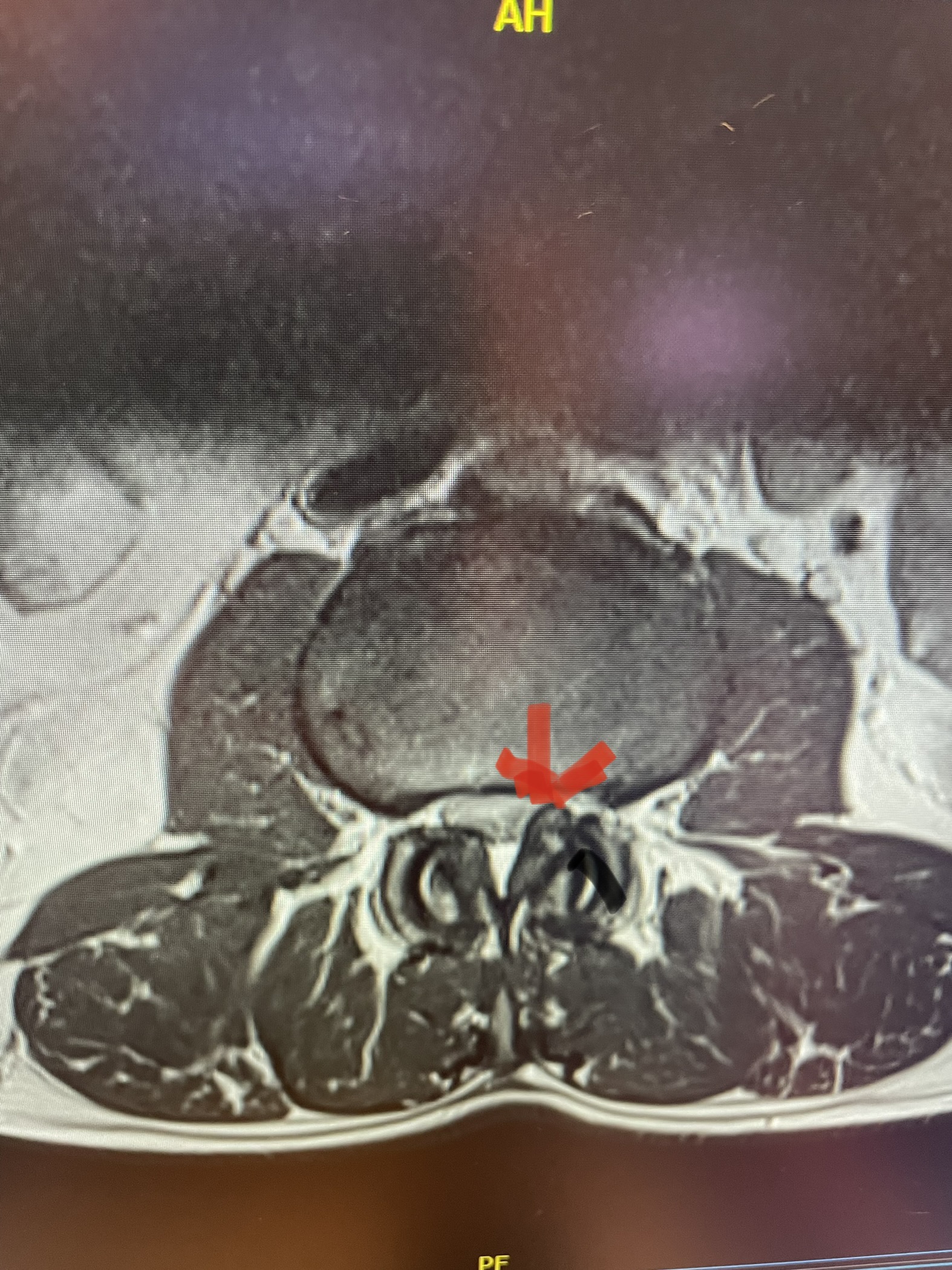

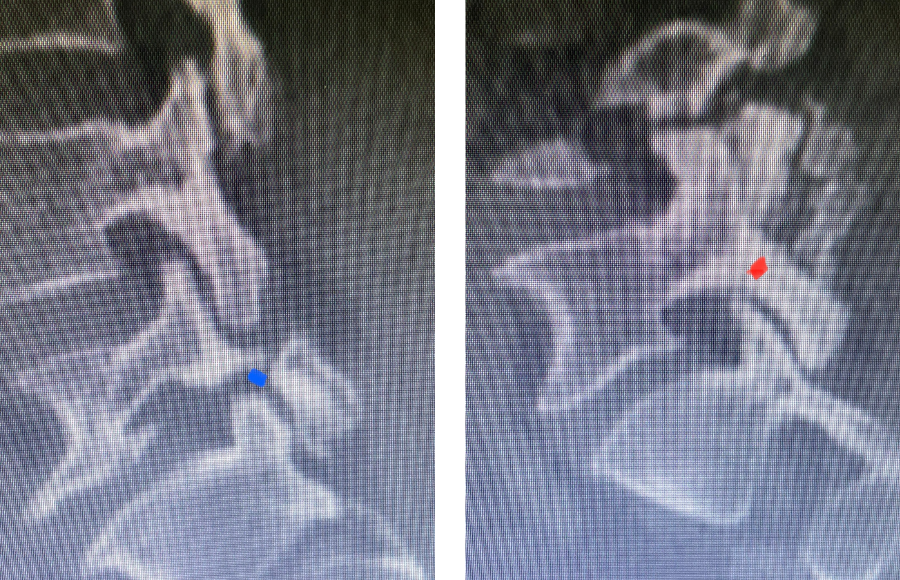

Fig 2: Sagittal T2-weighted MRI of the lumbar spine demonstrating a dysmorphic, trapezoidal-shaped L5 vertebral body (red dot) and a subtle grade 1 spondylolisthesis L5-S1 (blue line).

Plain lumbar x-rays were done with flexion/extension views. Surprisingly the patient had 4 mm of anterior translation and slight angulation in flexion (Fig 1). This was unexpected because in degenerative spondylolisthesis the patient more commonly has auto stabilized by formation of stabilizing arthritic structures and has no motion on dynamic x-rays. However, approximately 20% of patients will have some degree of translation on flexion-extension x-rays with degenerative L4-5 spondylolisthesis. Because she had failed all means of conservative management, it was felt that the patient would benefit by a lumbar decompression and instrumented fusion because of the acute instability demonstrated on x-rays and her age.

Fig 3: Sagittal CT scan with bone windows demonstrating an L5 pars defect (blue dot) and abnormal L5-S1 facet complex as well as a normal right pars structure of L5 (red dot).

Another interesting 54-year-old patient presented with low back pain and severe left lower extremity pain over two months. He had a history of falls. The pain in the leg was more bothersome to the patient. The patient had a work-up with an MRI and CT of the lumbar spine. MRI demonstrated a subtle grade 1 spondylolisthesis L5-S1 with a dysmorphic L5 vertebral body (Fig 2). There was a suggestion of a left L5 spondylolysis or defect in the bridge of bone that connects the superior facet process of the segment and the inferior facet process. A CT of the lumbar confirmed this unilateral abnormality which certainly could account for the patient’s left leg pain (Fig 3). This is an unusual finding in that most patients have bilateral pars defects. Patients with L5-S1 often have congenital abnormalities of the lumbosacral junction including weird shaped, elongated or dysplastic facet joints. A subtle L5-S1 spondylolisthesis with an associated smaller and misshapen L5 vertebral body is often associated with L5 spondylolysis. In addition, with a dysmorphic L5 vertebral body, there is secondary disc degeneration at L5-S1 and sometimes at the L4-5 disc with an associated retrolisthesis at L4-5. There is less surface to surface contact of the L4-5 and L5-S1 leading to chronic segmental instability.

It was recommended for the patient to have a targeted epidural to focus on the left L5 root, as this is generally the main nerve root involved in L5 pars defects as not only is there foraminal stenosis as a result of the shift forward of L5 on S1, but there is a buildup of thickened inflammatory tissue that builds up at the defect itself that compresses the exiting L5 nerve root. We will now wait to see how the patient responds to the epidural. It is difficult to participate in PT when you have severe radiculopathy.

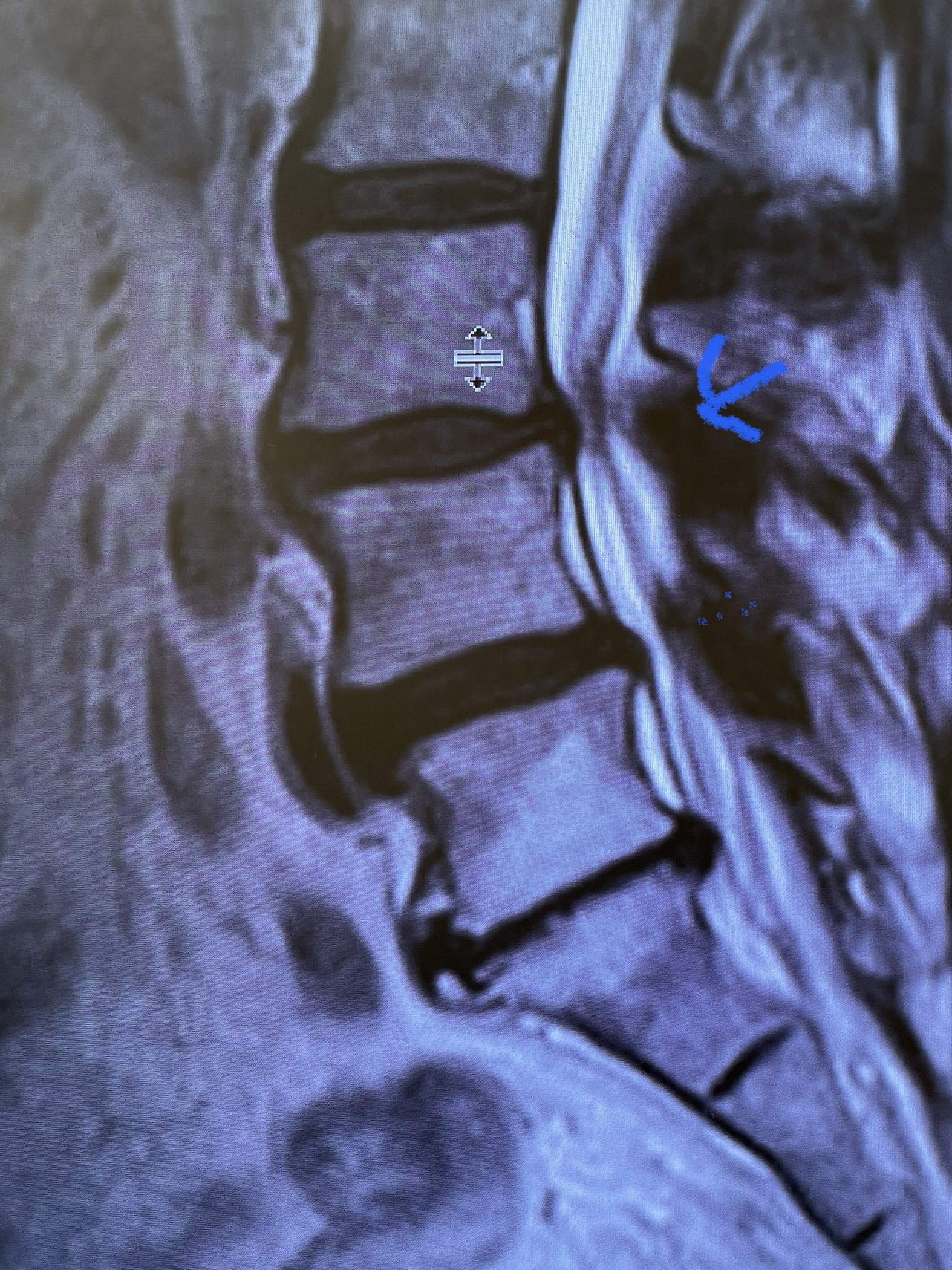

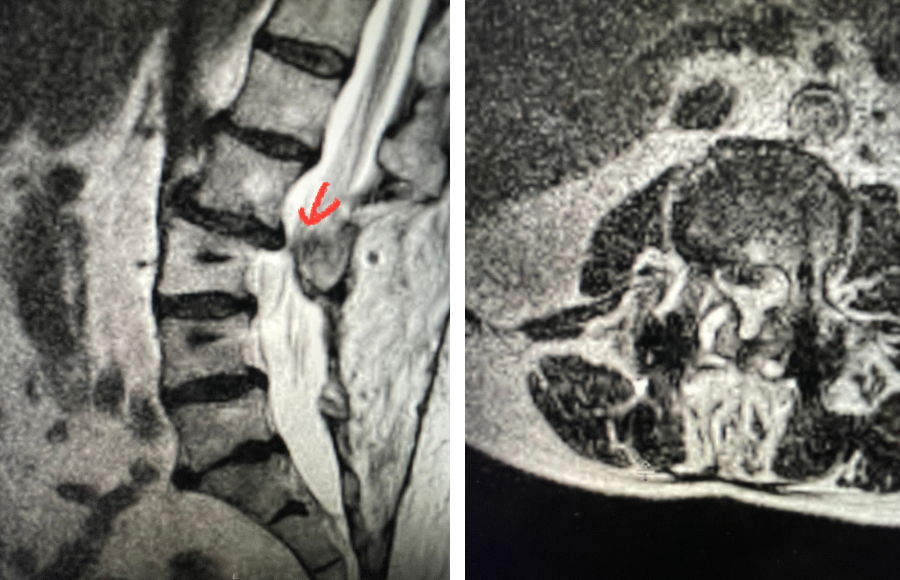

Here is a dramatic example of a patient who had prior laminectomy and fusion surgery four years earlier, and now presents with low back pain with severe burning pain in her right lower extremity pain. She did not respond to epidural steroids. She had a prior L3-S1 laminectomy, and an L3-5 instrumented fusion. A current MRI (Fig 4) demonstrated severe L2-3 next segment stenosis due the development of massively hypertrophied or enlarged L2-3 joint complexes. There was also a grade 1 retrolisthesis of L2 on L3 with a large anterior disc osteophyte complex. The configuration of the stenosis was worse in the right lateral recess secondary to the anterior osteophyte and more right-sided facet compression of the thecal sac, correlating with the patient’s right-sided symptoms. When the anatomy correlates with the patient’s symptoms that is the best set up for success. It was decided to offer a revision surgery to the patient, who agreed.

Fig 4: Sagittal and axial T2-weighted lumbar MRI images demonstrating severe next segment degeneration and stenosis at L2-3 above prior L3-5 fusion. Note retrolisthesis and significant facet arthropathy at L2-3 (red arrow).

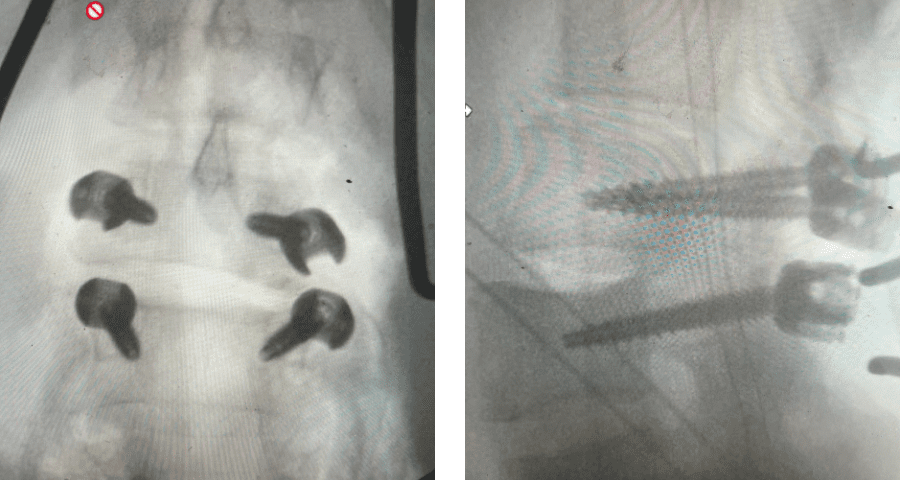

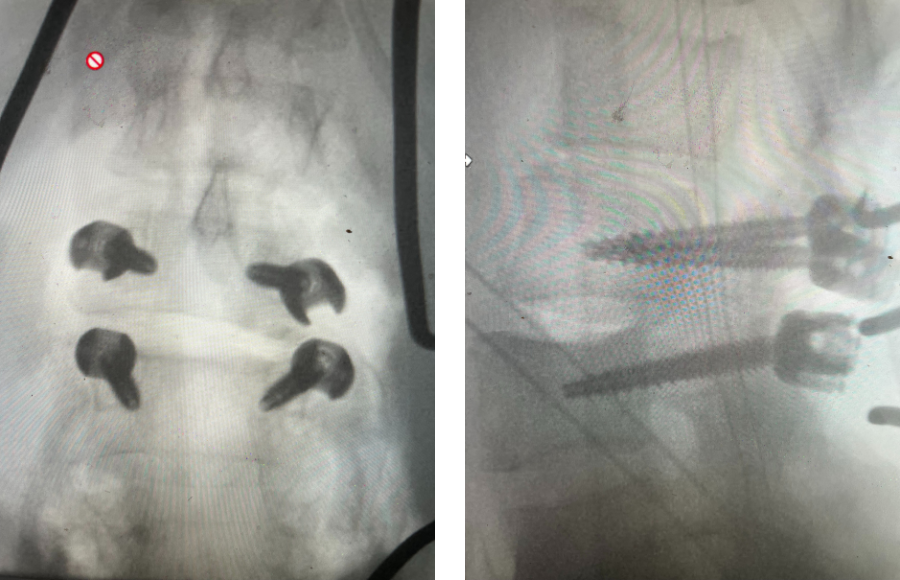

Revision surgery is more involved than primary surgery. In order to start decompressing this large complex, you must develop a plane; you have to find the edge of sometimes a remnant of a lamina or the lamina that can be buried in scar. You must carefully dissect the edge with a sharp upbiting curette and then either using a sharp Leksell to start removing this lamina or use a fine Kerrison to widen the plane and exposure and begin to expose the normal ligamentum above. In this case it was critical to expose and decompress the L3 nerve roots bilaterally. What is quite helpful is finding the inferior edge of the L2 facets. Then one must lift up the inferior L2 process up with a curette and simultaneously insert a Kerrison into joint space and remove the whole facet process. This is a great move because it allows access to the plane between the superior facet and the descending nerve root and a starting point to fully decompress the nerve root. Because of scarring there often is not a clear plane in order to accomplish the decompression. Care is taken to make sure there is a clear separation between edge of bone and dura during the process of inserting a Kerrison edge. The important part of this is feeling your opening and actually using your Kerrison as a dissecting tool once an edge has been established to perform a foraminotomy. We were able to remove the inferior L2 facet process with impunity as we knew we were performing an instrumented fusion to L2. The patient’s had a prior L3-5 instrumented fusion which upon exploration was solidly fused. It was decided to remove her prior hardware as it served its purpose and add a short segment from L2-3 (Fig 5). Patient did well after her surgery with relief of her right leg pain.

Fig 5: intraoperative fluoroscopic images demonstrating L2-3 screw placement.