- PATIENT FORMS | REQUEST A CONSULTATION | CONTACT US

- 1-844-NSPC-DOC

Right Vertebral Artery Compression Syndrome

Fusionless Cervical Spine Surgery for Herniated Disc

October 27, 2021

55 year old woman with one year of progressive hearing loss in the left ear / Acoustic Neuroma

October 27, 2021Educational Goals: Learners will be able to recognize the symptoms that may suggest Vertebral-Basilar Insufficiency, and appropriately refer these patients to appropriate imaging, testing, and subspecialist for urgent management and treatment.

A 61 y.o. Man reports that approximately 1 month ago when he was reaching a top Shelf in his kitchen, he started experiencing dizziness and lightheadedness and slight loss of balance while looking up. Over the last month the symptoms have increased in frequency, now occurring every day, and can be reproduced by extended his neck resulting in disequilibrium, tinnitus, and near-syncope which resolve when returning to Neutral station. Patient can also reproduce the symptoms when his shrugging his shoulders producing lightheadedness as well as left gaze nystagmus. His past medical history is significant for a significant motor vehicle accident in 2014 which resulted in significant side to side whiplash injury. He had limited motion of his head to begin with due to diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis and posttraumatic arthritis with auto fusion of his C1-C4/5 cervical spine. To deal with chronic cervical occipital pain, he had undergone 2 neuro-stimulation procedures, one for his occipital headache which resolved, and 1 for cervical pain which has improved but persists.

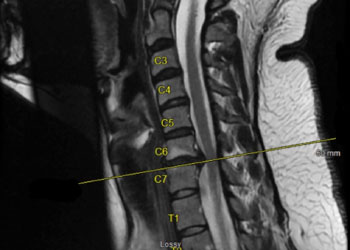

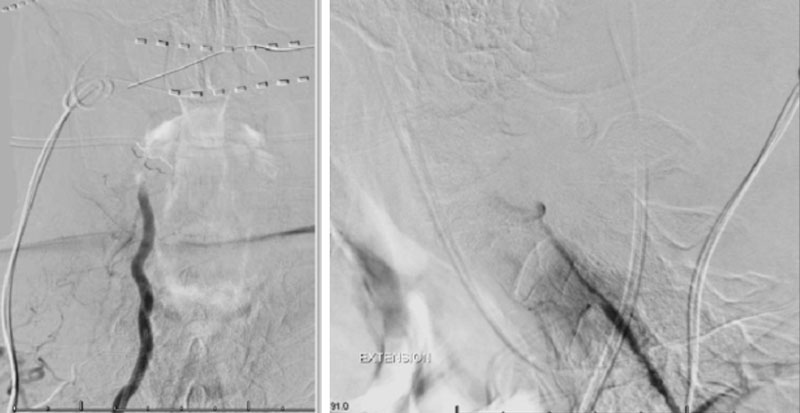

CTA of the neck and brain reveal that the left Vertebral Artery is completely occluded at approximately the C1-C2 level with extensive hypertrophic degenerative osseous changes from C1-C3. Retrograde flow into the post PICA left Vertebral Artery is observed from the co-dominant right Vertebral Artery which appears to be the primary supply into the basilar circulation. No significant Posterior Communicating arteries are observed on either the right or left Carotid Artery on the CTA imaging (Figure 1).

Dynamic provocative fluoroscopy failed to reveal significant Vertebral osseous instability (Figure 2A), however, Transcranial Doppler Flow velocities in the distal right Vertebral and Basilar Artery are markedly reduced during Extension of the Neck (Figure 2B).

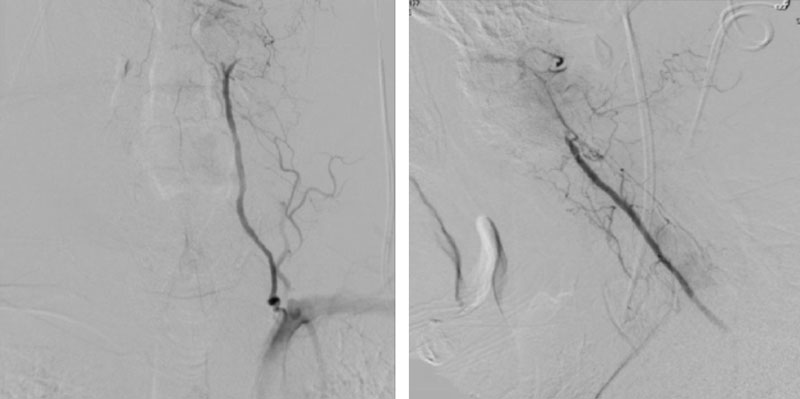

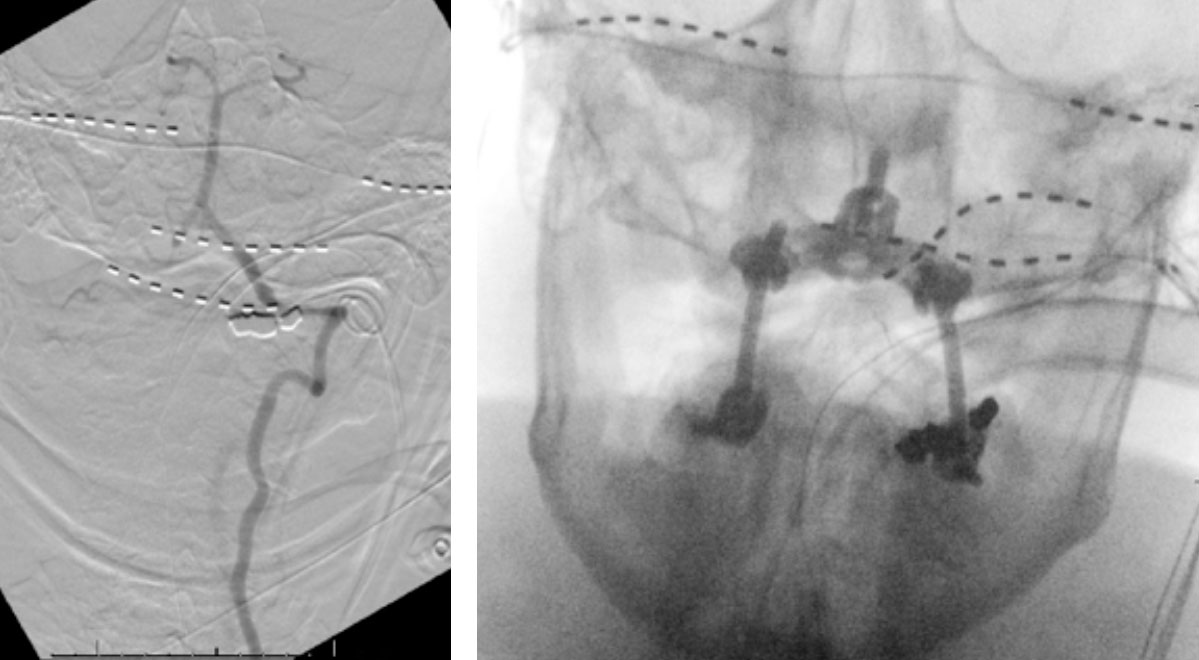

We performed conventional catheter angiography with provocative testing to reproduce his symptoms. The right Vertebral Artery is the codominant primary supply to the basilar circulation with reflux into the distal left Vertebral Artery that is occluded (Figure 3).

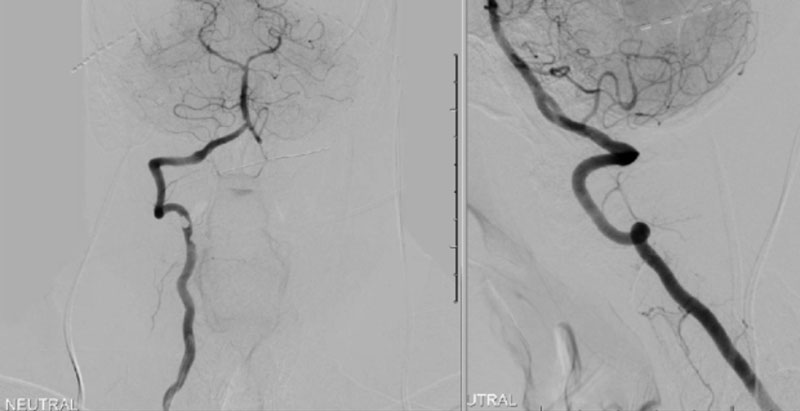

During neutral positioning, the vertebrobasilar circulation fills briskly from the Right Vertebral Artery. (Figure 4)

On rotation to the left, the patient experienced mild symptoms, however no significant Vertebral Artery or basilar reduction in flow was observed. On rotation to the right, the patient experiences slightly more moderate symptoms, however no significant Vertebral Artery or vascular reduction flow was observed. On hyper extension of approximately 10-15 degrees, passively performed by the patient until symptoms are reproduced, angiogram demonstrates complete occlusion of the right Vertebral Artery at approximately the C2-C1 level. (Figure 5)

It is unclear whether there is a specific bony osteophyte or soft tissue mass that is resulting in the compression. Live fluoroscopy within the neutral and extension position does demonstrate extensive arthritis and hypertrophic changes within the C1/C2 region, however specific anatomic compression is difficult to determine.

After extensive consultation and discussion of potential therapeutic and management strategies, we decided that permanent Occipital Cervical Fusion was the best approach to prevent potentially life-threatening Vertebral Basilar Occlusion during dynamic neck movements.

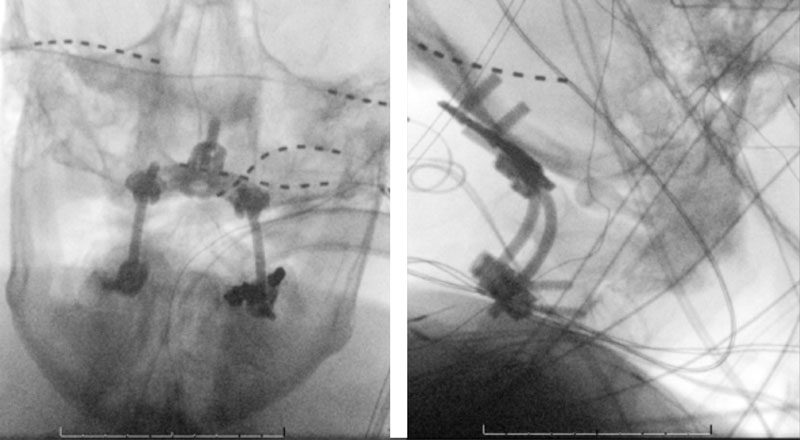

The patient was brought to the operating room, and general tracheal anesthesia was initiated via fiberoptic approach. Somatosensory potentials, motor evoked potentials, and brainstem auditory evoked responses were recorded. The patient then underwent intraoperative angiography of the right Vertebral Artery performed via a 5 French Right Radial Artery access. Once it was established that he had good flow, a Mayfield head holder was attached to the patient’s head on the 60 pounds of torque pressure. The Wilson frame attached to the Jackson table was then placed on top the patient attached to the Jackson frame. The patient was secured with straps and bed sheets and then positioned prone by rotating the frame around its axis. The flat plate of the Jackson table was then removed, and the patient bony prominences and soft tissues were adequately padded. Angiography was then again repeated showing good flow through the Vertebral Artery. After that, after being properly secured to the table with access to the right radial sheath, the neck and the left posterior iliac crest area and a tricortical autograft was then obtained with osteotomes. Iliac crest was reconstructed with fiber graft allograft. Posterior cervical incision was then performed and the spinous processes of C2 and C3 were identified and cleared of the fascia and then the muscle the way to the lateral edges of lateral masses. The C1 posterior ring was completely subluxed under the occiput and C2 lamina. The patient evoked potentials remained stable. The C1 lamina was then cleared of the soft tissue laterally on both sides. On the left side, significant osteophyte formation was visualized, and the C1-2 foramen was completely closed by the bone. On the right side, the C1-2 foramen was dissected, and the veins were coagulated with bipolar cautery. The C2 nerve root was identified and then coagulated bipolar cautery and divided with micro scissors, completing the planned C2 rhizotomy. The decision was made to perform an occiput to C3 fusion, since the articulation between the occiput, C1, and C2 was technically difficult and most likely would result in an inadequate fixation. At that point, a small occipital plate was brought into the field, and secured to the suboccipital bone with 14- and 12-mm screws. Then a pilot hold was created into the lateral masses of C3 bilaterally. The C3 appeared to be solidly fused to C2. First a hole was made with the drill and then passes were made with 40 mm drill with the guide. There were palpated with a ball-tipped probe and tapped. After the replaced 14 mm lateral mass screws into the lateral masses of C3 bilaterally. After the rods were fashioned and secured to the screw heads and the occipital plate with locking caps. (Figure 6)

Intraoperative angiography was then repeated again, showing good flow through the right Vertebral Artery into the Basilar Artery. Intraoperative fluoroscopy was then also performed to confirm good position of the screws and rods in both AP and lateral projections. (Figure 7)

Motor evoked potentials, somatosensory potentials, and brainstem auditory evoked responses remained stable throughtout. After that suboccipital bone, C1 lamina, C2 lamina and C3 lamina were decorticated with a drill. Extra small infuse kit and autograft bone were then placed over the decorticated bony surfaces, and the wound was closed. He was then placed into a cervical collar and awoken and extubated with stable neurologic exam.

He experienced a routine post-operative course and was discharged in good condition with cervical collar and pain management for 6-8 weeks to allow for fusion and healing.

Discussion:

Cervical vertigo is a syndrome characterized by vertigo, dizziness, and blurred vision with head Rotation or Extension compressing the Vertebral arteries leading to symptoms of vertebrobasilar insufficiency. Cervical spondylosis provided the initial model for Vertebral Artery compression. Sheehan et al., in 1960, published reports of a series in which 5 of 26 patients with cervical spondylosis and symptoms of vertigo and blurred vision with head rotation demonstrated Vertebral Artery compression as revealed by angiography.1 A similar syndrome related to intermittent compression of the Vertebral Artery by the anterior scalene muscle was described by Powers et al2. Since then, there have been many cases of symptoms related to compression of the Vertebral Artery, which can be secondary to unco-Vertebral bony spurring, muscle and tendinous insertions, or cervical subluxation and instability which have been often collectively termed bow hunter’s syndrome.3

The etiology of these syndromes is varied and have been reported to be associated with diffuse idiopathic or post-traumatic hyperostosis (as in our patient), rheumatoid subluxation, os odontoideum, surgical positioning, chiropractic manipulation, physical activities, and sports.4,5, Vertigo or near-syncope is the leading symptom of these syndromes which is usually attributed to brainstem ischemia and associated dysfunction. The labyrinth is also vulnerable to transient ischemia which can result in clockwise tortional downward beating nystagmus and unilateral tinnitus.6

To demonstrate the cause and location, dynamic or “provocative” angiography is required to reproduce the symptoms, demonstrated the location and source of compression, and confirm the diagnosis. Care must be taken to visualize contrast extending to the level of the foramen magnum to avoid incorrectly identifying too proximal of an occlusion secondary to delayed contrast during occlusion of the vessel distally.

After a diagnosis is confirmed, several options including conservative approaches (cervical collar) or surgical approaches can be considered. Surgical therapy must be tailored to the source of occlusion and may include fascial decompression, osteophyte removal and unroofing of the foramina, or in cases of subluxation and instability – surgical fusion. As described in our patient, the level of occlusion occurred at the Occiput-C1/C2 level secondary to subluxation of C1 at the level of the Foramen Magnum which necessitated cervical fusion. In the absence of his contralateral left Vertebral Artery, avoiding direct surgical manipulation and potential damage to his dominant/isolated Right Vertebral Artery supply, necessitated extreme care during his surgical fusion and instrumentation to avoid the course of the vessel thru the lateral masses of C2 and intraoperative angiography during the critical stages of his fixation (supine post intubation, rotational proning, and prior to final fixation of his instrumentation).7,8

Reference:

- Sheila Sheehan, Raymond B. Bauer, John S. Meyer. Vertebral Artery compression in cervical spondylosis: Arteriographic demonstration during life of Vertebral Artery insufficiency due to rotation and extension of the neck. Neurology Nov 1960, 10 (11) 968; DOI: 10.1212/WNL.10.11.968

- Powers SR, Drislane TM, Nevins S: Intermittent Vertebral Artery compression: A new syndrome. Surgery 49:257-264, 1961.

- Sorensen BF: Bow hunter’s stroke: J Neurosurg 2:259-261, 1978.

- Kuether TA, Nesbit GM, Clark WM, Barnwell SL. Rotational Vertebral Artery occlusion: a mechanism of vertebrobasilar insufficiency. Neurosurgery. 1997;41(2):427-433. doi:10.1097/00006123-199708000-00019

- Buntting CS, Dower A, Seghol H, Kohan S. Os odontoideum: a rare cause of syncope. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12(11):e230945. Published 2019 Nov 28. doi:10.1136/bcr-2019-230945

- Strupp M, Planck JH, Arbusow V, Steiger HJ, Brückmann H, Brandt T. Rotational Vertebral Artery occlusion syndrome with vertigo due to “labyrinthine excitation”. Neurology. 2000;54(6):1376-1379. doi:10.1212/wnl.54.6.1376

- Nagashima C. Surgical treatment of Vertebral Artery insufficiency caused by cervical spondylosis. J Neurosurg. 1970;32(5):512-521. doi:10.3171/jns.1970.32.5.0512

- Matsuyama T, Morimoto T, Sakaki T. Comparison of C1-2 posterior fusion and decompression of the Vertebral Artery in the treatment of bow hunter’s stroke. J Neurosurg. 1997;86(4):619-623. doi:10.3171/jns.1997.86.4.0619

Disclosures:

The planners and faculty participants do not have any financial arrangements or affiliations with any commercial entities whose products, research or services may be discussed in these materials.

CME Accreditation:

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the accreditation requirements and Policies of the Medical Society of the State of New York (MSSNY) through the joint providership of the Academy of Medicine of Queens County and NSPC Brain and Spine Surgery. The Academy of Medicine of Queens County is accredited by The Medical Society of the State of New York (MSSNY) to provide continuing medical education for physicians. The Academy of Medicine of Queens County designates this Enduring Materials for a maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ as specified in this activity. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Authors

To learn more about the author, click his name or photo: