- PATIENT FORMS | REQUEST A CONSULTATION | CONTACT US

- 1-844-NSPC-DOC

Lateral Disc Herniations

Thoracic Stenosis

July 22, 2022

Revision Lumbar Surgery

October 6, 2022

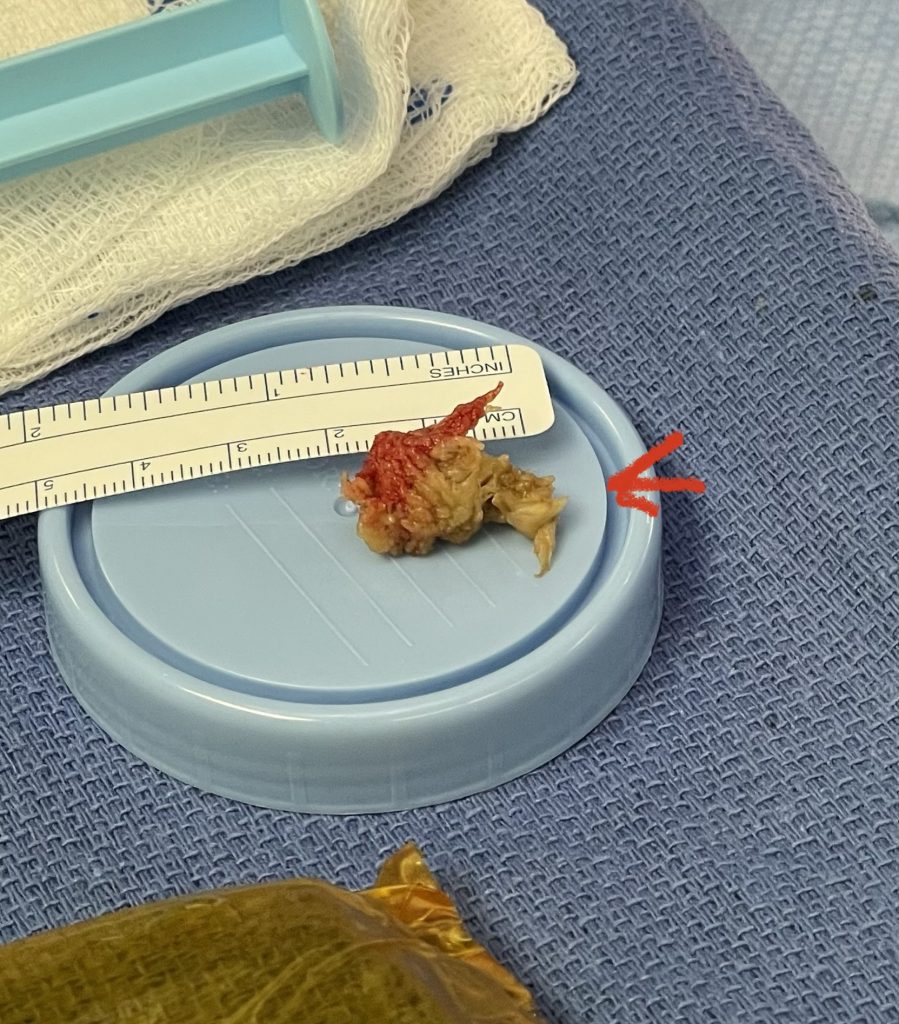

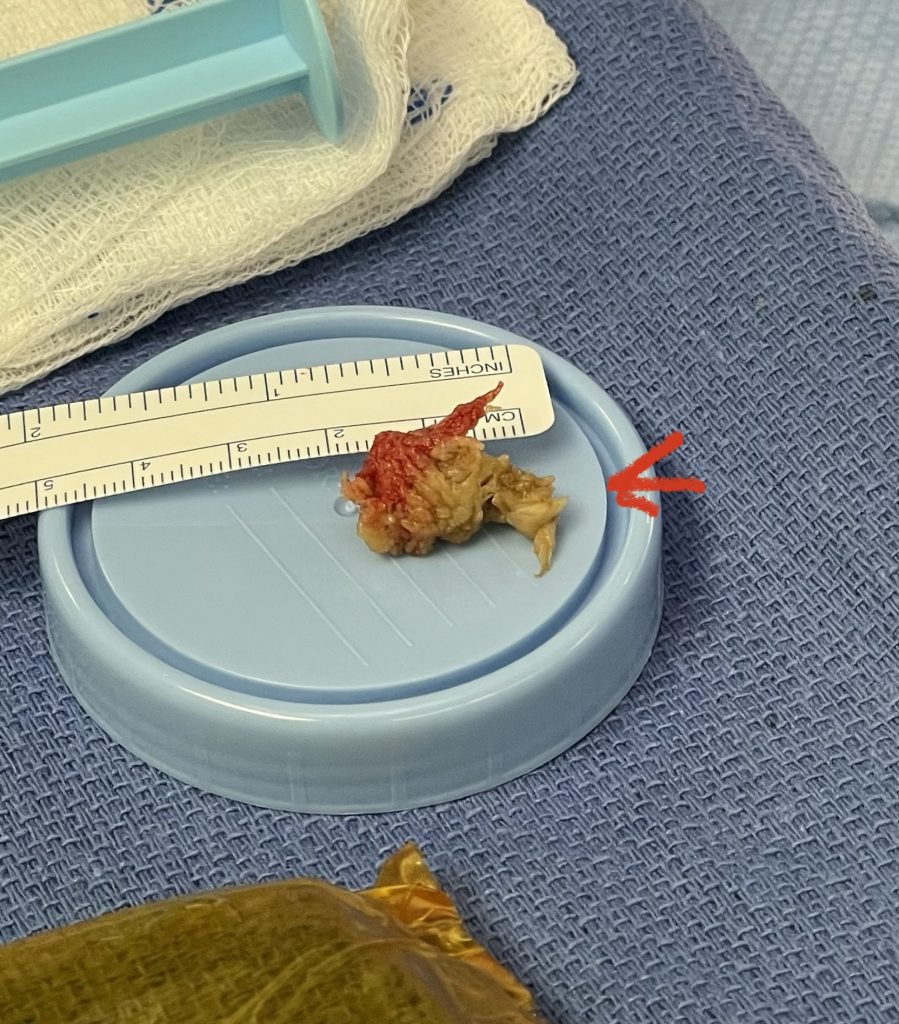

IMG 6060

Patients can present with all kinds of herniated discs that occur in many different locations in the lumbar spine. I tell patients that the disc is like a jelly donut and that the jelly is the material that comes out because of a tear in the donut. Actually, if you touch the disc fragment in the operating room it feels more like crab meat to me. Sometimes the jelly comes out completely, or sometimes it bulges out but is still contained in the donut. Even if it is contained, it can still cause pressure. Depending on where the weakening in the donut is will determine whether the jelly goes to the center or way off to the side. If it comes down to surgical removal of the disc fragment, we only remove the part that is pressing, not the WHOLE disc!

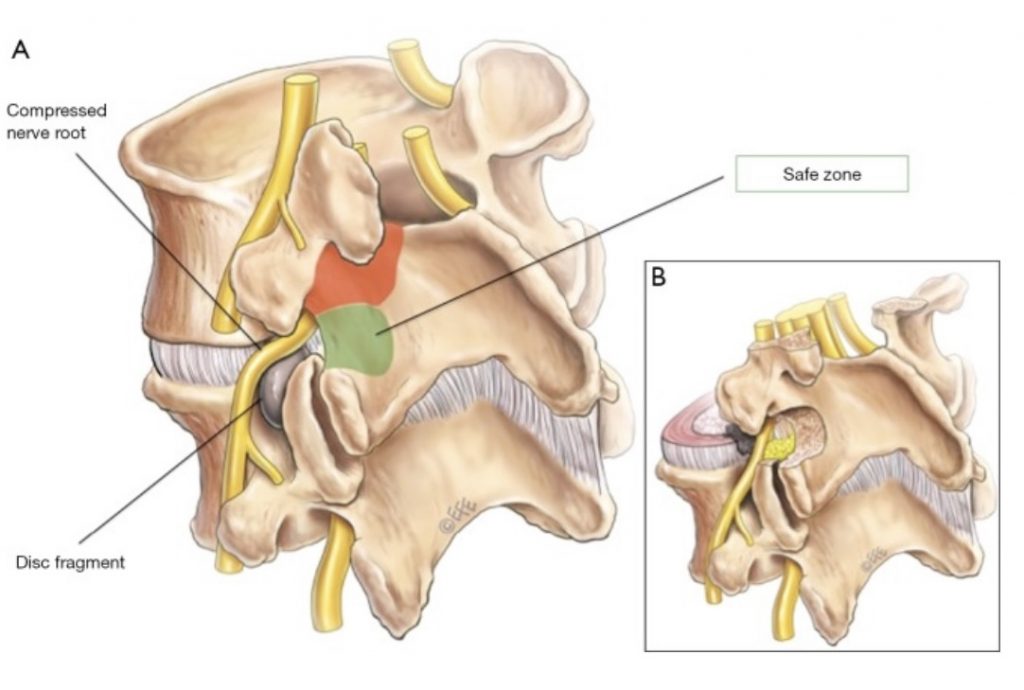

Fig 1. Figure illustrating compression of the exiting nerve root by a far lateral disc herniation.

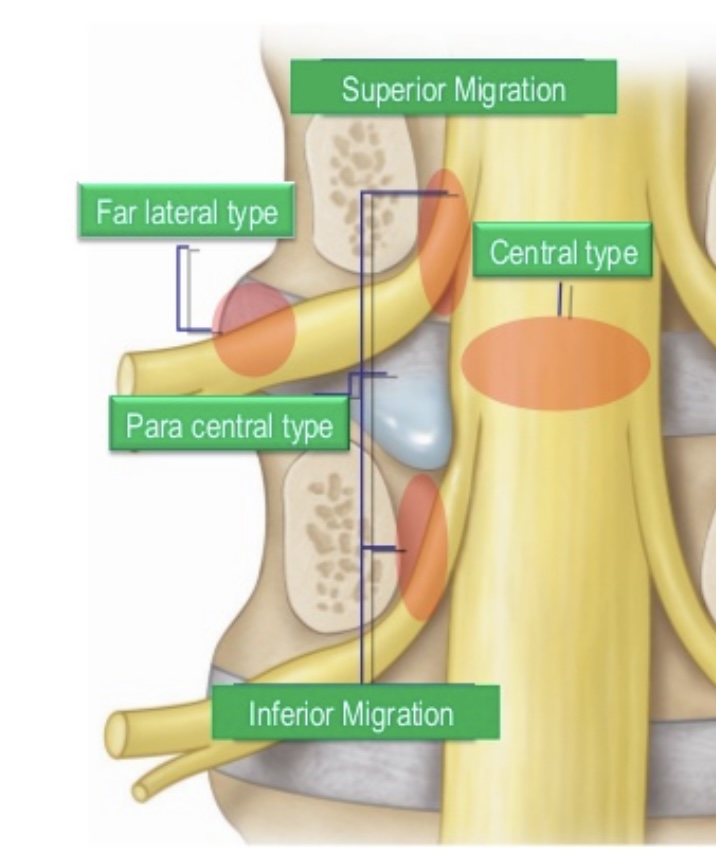

Fig 2. Cartoon showing how a paramedian disc herniation misses the superiorly exiting nerve root but compresses the descending root.

Most disc herniations are paramedian and tend to affect the descending nerve root. An L4-5 disc herniation that is just off the midline will affect the L5 nerve root descending on that side; the L4 nerve root has already exited above. Some disc herniations, however, are more unusually lateral and affect the nerve as it exits the foramen. Some can be contained within the foramen, and some are so far lateral that they become extraforaminal and beyond the facet complex. If a patient has an L3-4 far lateral disc herniation, it will affect the exiting L3 nerve root, not the L4 because in the lumbar spine the L3 nerve root exits the L3-4 foramen. Far lateral disc herniations are often superiorly oriented, for which they compress the exiting nerve root against the bone of the pedicle (Fig 1). With an L3-4 paramedian disc herniations, the L3 nerve root has already exited (Fig 2).

Patients with far lateral disc herniations have particularly dramatic presentations with regard to pain and weakness. One reason could be that, in far lateral disc herniations, the foraminal compartment that they extrude into has much smaller dimensions. The disc herniation also pushes the nerve root against the bone as compared to a central or paramedian herniation, where the herniation occurs into a larger dimension, the spinal canal, and more cushion with the fluid-filled thecal sac.

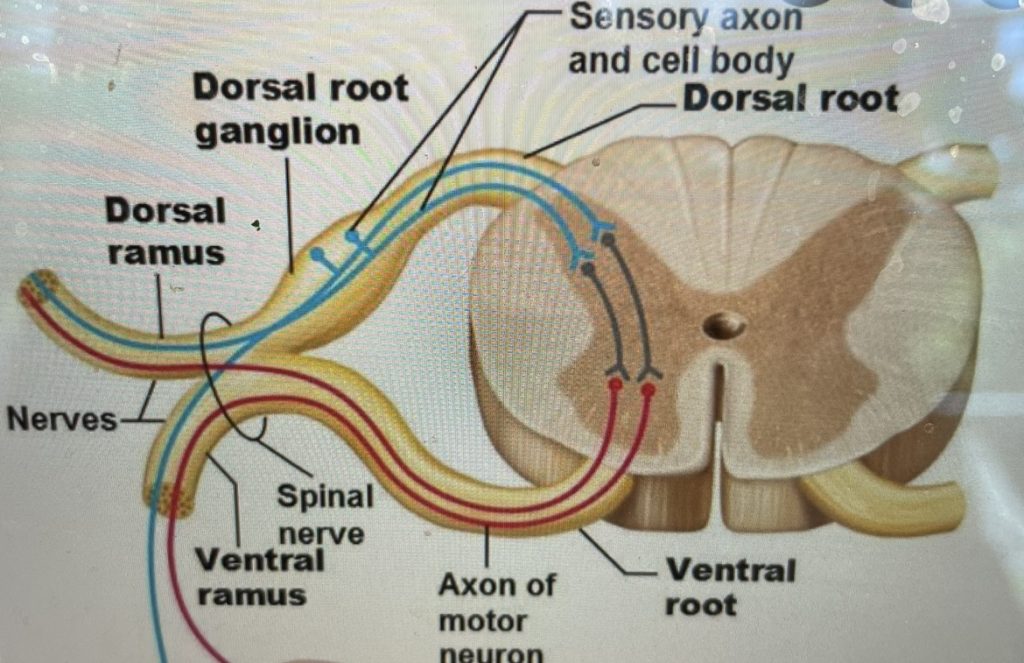

In addition, far lateral disc herniations are in proximity and compress the DRG (dorsal root ganglion) which contains nociceptive or pain-related unipolar cells with substance P, a chemical related to pain, as a neurotransmitter. Anatomically, the dorsal root and the ventral root coalesce to form the spinal nerve which exits extraforaminally (Fig 3). The dorsal root expands to begin to form the dorsal root ganglion in the foramen prior to the formation of the extraforaminal spinal nerve. As a result, patients can present with much more intense pain syndromes which is often responsible for the dysesthesias both transient and permanent that can occur with this type of pathology.

Fig 3: Anatomy the exiting dorsal and ventral nerve roots and the formation of the dorsal root ganglion within the neural foramen.

As an example of this type of pain syndrome, an interesting 58-year-old female presented with “soreness” and numbness of her left groin area for 6 months. She had no leg or back pain, weakness, or bowel or bladder dysfunction. She sought gynecological care, for which she had a pelvic examination. The examination elicited pain on left-sided palpation. She had negative imaging of her pelvis. Her family physician ordered a lumbar MRI, which revealed a left foraminal disc herniation compressing the left L1 root superiorly against the L1 pedicle (Fig 4). Clearly the numbness was in an L1 dermatomal distribution and correlated with the patient’s MRI. We started the patient on Medrol and Neurontin. We referred her to pain management for a left L1-2 transforaminal epidural and will follow her up in 6 weeks. If her problem does not resolve, we will offer surgical removal. It is important to realize that many patients with spinal pathology can present pain syndromes that mimic other conditions. For example, a patient may have an upper thoracic compression fracture with pain referred to the anterior chest wall, which can cause the patient to feel like they are having a heart attack. It is only during a cardiac workup that they discover the underlying problem with a chest x-ray.

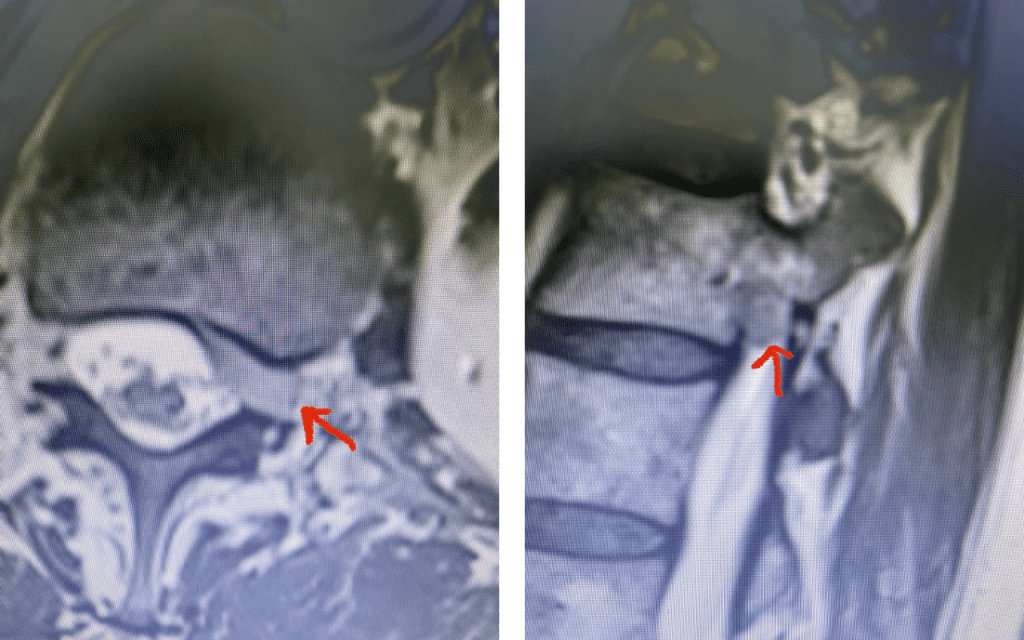

Fig 4: Axial and Sagittal T2-weighted lumbar MRI demonstrating a left lateral foraminal disc herniation (red arrow) causing compression of the exiting L1 nerve root against the undersurface of the pedicle of L1.

Those patients with a lateral disc who have failed conservative management and have symptoms and signs that correlate with their imaging studies are candidates for surgical treatment. A patient who presents with a far lateral disc that is extraforaminal and is lateral to the facet complex, a lateral approach can be accomplished. There have been numerous techniques described to access the disc herniation without having to perform a traditional hemilaminectomy. These are more minimally invasive, “muscle sparing” techniques through various corridors. In the end one must identify the lateral facet-transverse process junction of the inferior level of the spinal segment. At this junction there is a safe zone inferiorly after the intertransverse membrane is reflected. The far lateral disc is revealed in this inferior compartment knowing the exiting nerve is in the upper portion of this compartment. In order to gain exposure of the disc fragment, there is a “safe zone” of bony removal with confidence that the space that is revealed is below the nerve root (Fig 5). Sometimes the disc fragment is so lateral that one does not have to remove any bony to gain access. As in the case of the prior patient with the L1-2 foraminal disc herniation, a traditional approach of a left hemilaminectomy may be better suited, as the disc may not be able to be exposed laterally without removal of the pars and a significant portion of the joint to get access, destabilizing the segment. The important point about this approach is that if it is necessary in accessing foraminal discs from medial to lateral, one must identify the upper root which means that it is often necessary to remove the superior lamina as well and break the bridge to the next level. You must always expose higher than you think.

Fig 5: Illustration demonstrating region of safe bony removal and lateral disc removal from a lateral approach. The red zone is the compartment where the exiting nerve root is present and should be identified and protected as to prevent harm to the nerve.

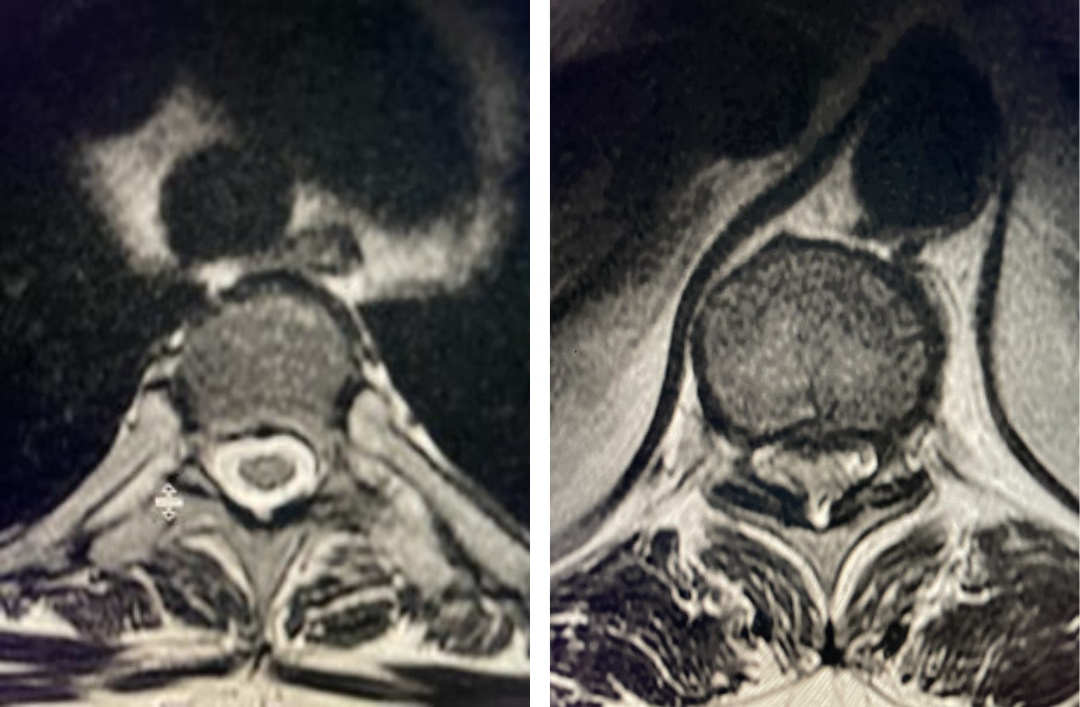

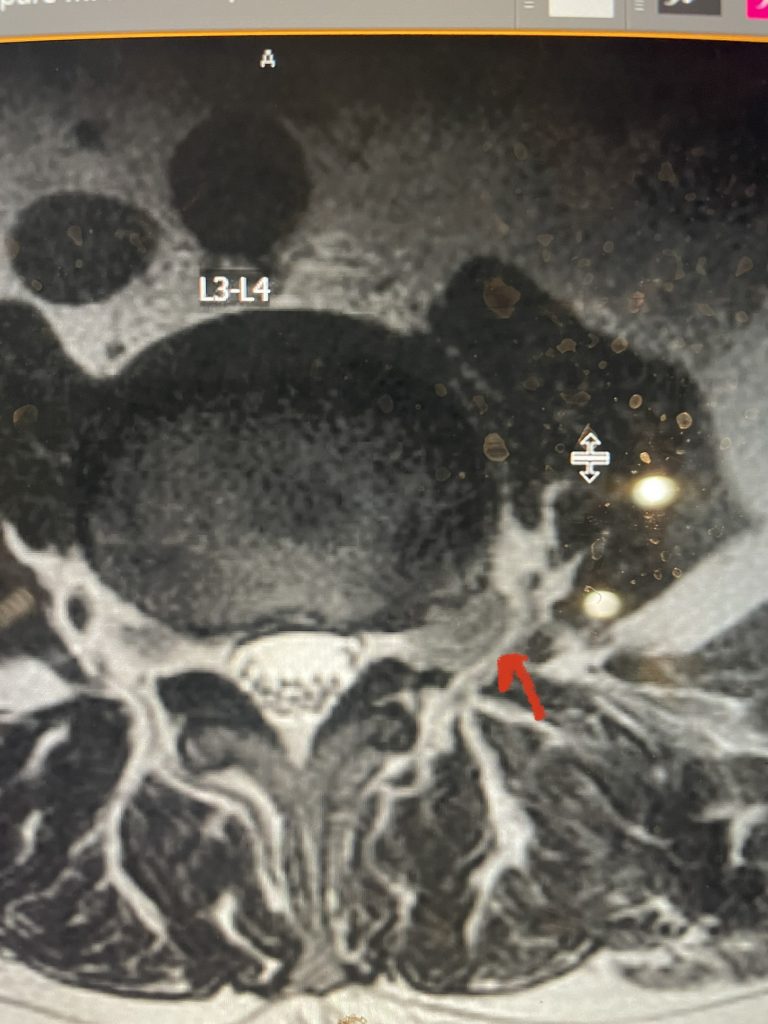

Fig 6: Axial T2-weighted lumbar MRI revealing a large extraforaminal disc herniation with severe compression of the left L3 nerve (red arrow).

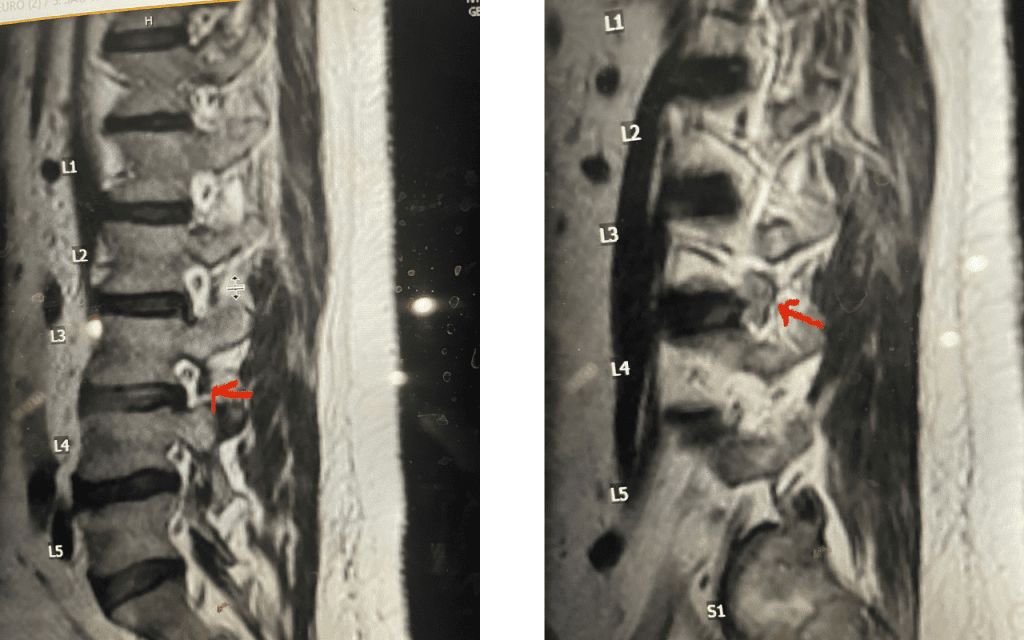

Fig 7: Sagittal T2-weighted lumbar MRI with side by side comparison of the normal open right L3-4 foramen (red arrow) compared to the left L3-4 foramen filled with a large disc fragment (red arrow).

Here is a case of an extraforaminal disc fragment causing severe pain and weakness: This 60-year-old male presented with severe anterior thigh pain, numbness, and weakness for 3 weeks. He had failed epidural steroid injections. His left leg buckled when he walked. Imaging revealed a massive left L3-4 extraforaminal disc herniation, beyond the facet (Fig 6). This was severely compressing the left L3 nerve root in the L3-4 foramen (Fig 7). It was felt that the patient required surgery, as he would not be able to participate in physical therapy and had a neurological deficit. We performed an extraforaminal approach and removed a massive disc fragment that was revealed as the intertransverse membrane was reflected from the L4 transverse process-facet junction. We were able to visualize the L3 spinal root exiting above that had been compressed by the large fragment we removed (Fig 8). The patient post-op had a dramatic improvement neurologically and with significantly improved pain in his leg.

Fig 8: Large extraforaminal disc fragment removed at L3-4 (red arrow).

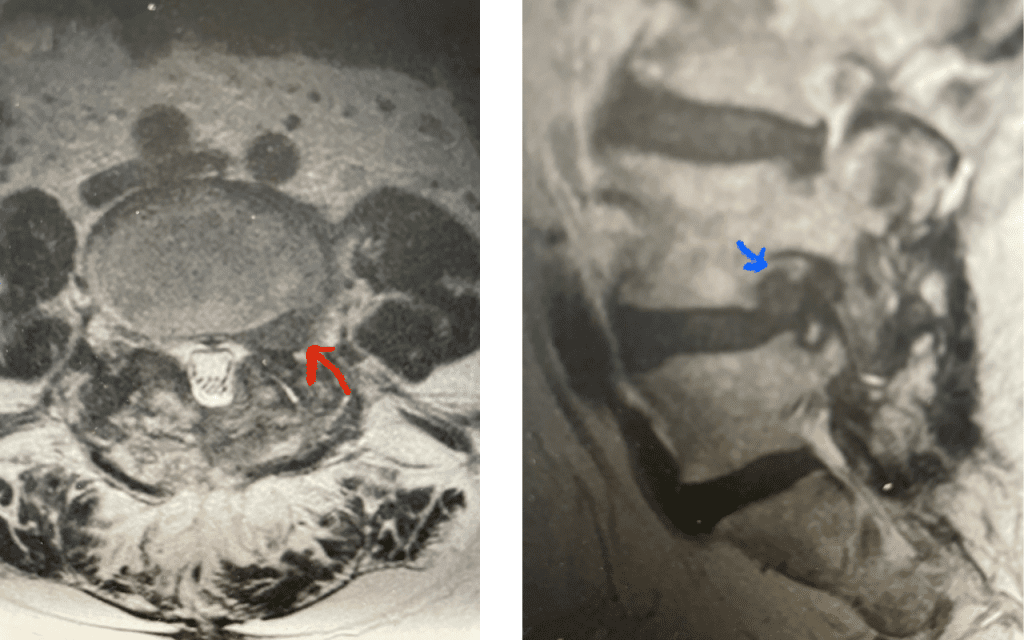

We had a recent flurry of lateral disc herniations. Another challenging case recently was a 76-year-old male who presented with 6 weeks of severe left anterior thigh pain, numbness, and weakness of his hip flexor and quadriceps, four years prior at L4-5 he had a removal of a large L4-5 synovial cyst on the right side of the canal and in situ fusion for which he had done very well. New imaging about a month prior revealed a new large far lateral disc herniation on the left side (Fig 9). The patient had mild spinal stenosis at this level and the cyst gone, but the disc on the left was extraforaminal at L4-5 compressing the left L4 nerve root. He had a trace spondylolisthesis. The patient underwent a series of epidurals with no improvement. Patient agreed to proceed with surgery. The laterality of the disc fragment made it amenable in our opinion for a lateral approach as to attempt a medial approach would be quite risky given the prior laminectomy and attendant scar formation which would increase risk for spinal fluid leak. The prior fusion mass was thin and incomplete and was removed easily with Kerrison punch. The main problem was the scarring in the intertransverse space and discerning the anatomy of the L4-5 facet complex. However, we remained in the “safe zone” and although the nerve was buried in scar tissue was not well identified, we were able to dissect enough to extract the disc fragment. This fragment was clearly pushing upward the scar tissue containing the L4 nerve root. We added an in-situ fusion with BMP because of the slight spondylolisthesis although we had to remove a minimal amount of bone in the safe zone for exposure. Fortunately, the patient had relief from his symptoms.

Fig 9: Axial and Sagittal T2-weighted lumbar MRI demonstrating left L4-5 far lateral disc herniation (red arrow). Notice how on the sagittal MRI the disc herniation fills the foramen and is superiorly oriented, compressing the left L4 nerve root against the L4 pedicle (blue arrow).